I wrote this puzzle in July 2023, so my memory of parts of the setting process is a little hazy. That said, the folder on my PC that I used for constructing it allows for a bit of archaeology, so I’ll outline the setting process here.

Of course, the hardest bit of setting any thematic puzzle is finding a decent theme that lends itself nicely to some sort of crossword treatment. I think I became aware of the Dorabella Cipher via a slightly roundabout route after reading about the comparatively uninspiring “Shugborough Inscription” (the letters OUOSVAVV between oddly placed letters D and M on a monument — no one knows why) after a visit to that rather charming National Trust property in Staffordshire. The article that I read linked to the Dorabella Cipher as another example of an unsolved old cryptography problem, so off I went down another enjoyable Internet rabbithole.

I found it quite amusing that several folks over the years have claimed to have decoded it, usually making some bizarre jumps in their logic or ending up with a message that’s scarcely more comprehensible than the squiggles themselves. The human tendency to spot patterns among noise seemingly knows few bounds, yet because Elgar was the author, many seem to think that the semicircles are somehow related to notes of the scale. This seems pretty unlikely to me, but no-one can be sure.

Among my amusement came an idea — maybe the 1, 2, or 3 semicircles represented jumping between cells in a grid of letters. Perhaps that’s what Elgar did; I didn’t bother to check whether I’d cracked the actual cipher since I was too busy constructing this damn crossword — surely that was more fun than trying to crack the original message! Anyhow, wouldn’t it be fun to reverse engineer a grid that took his unresolved enigma and make it say something? An idea was born — the hard bit was done.

One of the facts I found interesting about the Dorabella Cipher is that the same glyphs showed up over ten years prior in the so-called “Liszt fragment”, which strongly suggests this really was some kind of true encoding method rather than just trolling Miss Penny by sending her a load of random squiggles. There are some other scribblings by Elgar in existence that use the same symbols, one of which from his later years looks like an attempt to remember how the heck the bloomin’ thing works (it looks like he couldn’t really decode it himself by that point). I therefore thought I’d try to weave the Liszt fragment into the puzzle somewhere. Perhaps I could use the first line to point solvers towards the Liszt fragment, and then the Liszt fragment could instruct solvers to do something else, perhaps generate a message that could be written under the grid.

Having fixed the first message (USE LISZT FRAGMENT CELL STAR), which was the right length for the first line of the Dorabella Cipher (given that some cells are inevitably revisted), I made a corresponding grid with that message starting at a randomly chosen point (a grid corner) and barred it off in such a way that the gridfill was not all that restricted. This was mainly a case of barring between infeasible adjacent letter combinations and then trying to cobble together a grid structure from that that met, or closely met, the usual Ximenean requirements. The phrase UNRESOLVED ENIGMAS would fit nicely with the Elgar and cryptography themes, and was the correct length for a path traced by the Liszt fragment. The plan at this stage was to get solvers to write this under the grid. With a bit of rebarring, everything fitted without seemingly making the gridfill too restricted.

The next task was therefore to overlay this second message (the dispersed “UNRESOLVED ENIGMAS” in cells dictated by the Liszt fragment) onto what I already had. This was, it seemed, not straightforward. Two problems immediately arose:

1) the distribution of cells must not clash or overlap with the first message, so very many possible starting points for the second message were not feasible, and

2) after trying two or three valid starting points, QXW failed to find a gridfill.

Perhaps my idea wasn’t possible after all, or at least not without hours and hours of trial and error that might get nowhere. Something at the back of my mind then reminded me of the bit of QXW’s manual about its “batch mode”, which, simply put, lets you automate trying lots of things in a row. I’d never used it before, but it seemed like it may be the tool for the job, so now was the time to learn it. I therefore knocked up a little Python script that knocked together all possible (non-overlapping) placements for this second message, and churned out a QXW batch mode input file for each. QXW now crunched all of them, only to get the dreaded “No grid fill found” for each and every one. Disappointing perhaps, but at least I’d learned how to use a useful tool which I’ve since used in other puzzles.

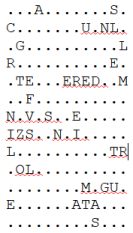

I still had one more thing to try before giving up — I hadn’t yet moved the first message’s starting point around the grid, having arbitrarily stuck it in the corner. More Python followed, this time churning out 2703 QXW input files that batch mode churned through (with the same barring as before) over a lunchtime. “No grid fill found” appeared again (2703 times — delightful). It had been too optimistic to think something like that would work without rebarring. However, my Python code also gave me output like this (2703 times):

From such output, I could eyeball possible placements of the messages that didn’t have a load of horrible letters near each other, with the symmetrically opposite bit of the grid not being too constrained, so as to leave a reasonable chance of a gridfill. Then I could play around with barring. In all honesty, this bit of setting the puzzle wasn’t that scientific beyond developing a general feel for which parts of the grid were insanely restricted and which bits were merely very restricted(!), but after 10 minutes or so of playing around, I had a sufficiently Ximenean barring and suitable average word length that seemed to give me a gridfill with both messages in place. Hurrah! It was the 150th of 2703 possibilities that caught my eye as it had L…..ERED along the top, which seemed to use up a reasonable number of imposed letters in a nice arrangement, while importantly also having lots of completely free cells opposite where a long word could go. After all, having too low an average word length quickly becomes a concern in super-constrained constructions like this.

My happiness was interrupted by a brief moment of abject horror and panic (evidenced in my archaeology by the now amusing filename “150_BAAAH_NOOOOO.qxw”) when I then realised I’d mistranscribed the very final symbol’s direction, so I had created something like UNRESOLVED ENIGMAF. Blast! By a miraculous piece of good fortune, the correct direction threw the traced path into the very central cell of the grid, where I seem to remember I had a three letter entry at this point, which wasn’t doing me many favours as far as the average word length was concerned. Mercifully, this was rescued by replacing that with a completely barred-off empty cell, which doubled as an opportunity to make solvers prove that they’d followed the whole path to put the final S in this cell (this edit appears in the much more relaxed-sounding “150_ACTUALLY_FINE.qxw” with a timestamp three minutes after the previously mentioned one). A “happy accident”, as Bob Ross would say.

With a bit more careful tinkering (well, actually quite a lot), I could even crowbar the words ENIGMAS and UNRESOLVED into the gridfill, which could be highlighted. This seemed a really pleasing and improbable bonus — much more elegant than writing it under the grid. I struggle to emphasise here just how constrained the gridfill was to get this working… the construction was very nearly impossible I think. Seeing RHEIDOL forced by the filler as one of the entries was the icing on the cake for me as that particular river — obscure to some, perhaps — runs through the field behind my house!

So there we have it — construction complete. Clue writing then took place (not my forte but hopefully I’m slowly improving), with extra words directing solvers towards Dorabella. My favourite clue was my &lit for 30d (ARETES) and I was thankful that the editors allowed me to keep 14ac: “FA reportedly flog trophy (5)” despite its use of the more vulgar definition of FA as a wordplay element which I suppose someone of a particularly prudish nature may manage to be offended by.

The most worrying aspect of the Dorabella Cipher, perhaps even a possible reason for editorial rejection, was the ambiguity of the symbol’s directions; it’s hard to say with certainty whether a few of them are at an angle or not. For this reason, I thought that even/odd lengths of extra words could be used to disambiguate the orientations (I’d had this mechanism in mind fairly early on and tried to make sure that the number of entries matched the number of extra words needed as closely as possible). I figured that most solvers would likely not bother with the odd/even nature, but would just backtrack if an ambiguous orientation started generating gobbledegook, but it seemed only fair to include some mechanism to help with the interpretation. The title, Romantic Piece, was a nod to “Liszt fragment” (a fragment of Liszt would be a Romantic piece) and the possibility that the message to Miss Penny may have had a romantic nature, although it seems that their relationship was likely more of an emotionally rich friendship. That said, why encode a note if its contents aren’t at least a little “interesting”? Until it’s decoded though, it’s anybody’s guess — it might have just been his shopping list?

My test-solver, former Solver Silver Salver winner Andy Nelson, to whom thanks are due for his feedback and suggestions, just about limped over the finish line, seemingly impressed with the construction but a bit irked by the fiddliness of the endgame. I suspected he would not be the only one to share such a judgement. Of course, I’ve been on the solving end of these kinds of puzzle where you think “nice construction, very clever, but did you have to put me through that?” before, but I think (or perhaps hope?) that the “nice construction” bit of that message is what tends to live longer in the memory, so hopefully it didn’t drive too many solvers to fury — apologies if it did! Regardless of any torment inflicted upon the solving community, it’s my favourite puzzle that I’ve set — so far at least.

As ever, immense thanks are due to Roger and Shane for their truly superb editing. Non-setting solvers may not be aware of the extent to which the space available in the paper for the Listener makes conciseness (or concision as they write in their vetters’ reports — it’s a shorter word after all!) in clues and preamble vital. Cutting down my original preamble to such a short version without losing much is very impressive, as are their adjustments to my clunky clues. Thanks also to Neil for marking and forwarding feedback and to all solvers who have commented on the puzzle. Among these is Dmitry Adamskiy whose <a href=”http://<a href=”https://www.youtube.com/@mityaadamskiy”>YouTube channelmityaadamskiy channel might be of interest for Listener afficionados. I was previously unaware that Dmitry was doing short video reviews of each Listener — a great idea!